Sometimes, the archives unexpectedly offer a treasure of distant voices from the past. Last week, when I was reading Frances Gouda’s 1995 book Dutch Culture Overseas, I discovered that she had used some letters by female Indonesian students of the privately funded Van Deventer Schools in Solo and Semarang in the late colonial period. I figured this would be a nice source for me to look into, because I am currently writing a chapter on social provisions in the Dutch Empire, with a specific focus on labour legislation and the provision of general education.

So, yesterday morning, I went to the National Archives in The Hague to check this out. And what a treasure it was: dozens of letters written by Indonesian girls in their teens, to the matron of the Van Deventer Schools to express their gratitude to her at the moment of their graduation. It is pretty clear that the girls were probably instructed by their teachers to write to the elderly mrs. Elisabeth van Deventer-Maas, who by then was widowed and resided in the Netherlands. For certain years, almost all graduates wrote a small letter, and all letters contain similar elements, such as thanking mrs. Van Deventer for the present she sent the girls (a silver pencil), and describing the festivities surrounding the graduation ceremony.

Nevertheless, many of the letters also contain highly personal, sometimes really moving writings, which give a lively snapshot of the preoccupations of young minds of Javanese educated girls in the early 1930s. For sure, these girls did not form a representative sample of the indigenous female population. They were at least from the middle classes, and sometimes priyayi (elite). They had learned to read and write the Dutch language fluently, and were taught ‘womanly’ skills such as embroidering and housekeeping according to ‘Western’ values of domesticity. Many of them dreamed of a future in which they would have a working life, in which they would pass on all of the things they had learned in school to other Javanese children. Saparti, for instance, wrote: “And now I will exit the gate [of the institution – EvNM] and enter into the world to try to teach my knowledge to the Javanese people”. Sri Martini, in turn, specifically expressed the wish to “transfer all the good, that I have learned here, to other Javanese girls and women”.

Moehilah was a bit less selfless, and displayed her deep desire for autonomy, when she stated “Oh, to earn my own bread used to be my burning wish, and now it is accomplished. Wonderful, that my sweet parents no longer take care of me.” In a similar vein, Saleha from Batavia (present-day Jakarta) wrote “You might wonder, why I did not go to school in Batavia? Yes, dear Ma’am, I am a girl that favours to enjoy the world. Since I am the youngest daughter of my parents, and I could decide for myself where to go to school, I immediately chose this school, of which I had heard so much good.”

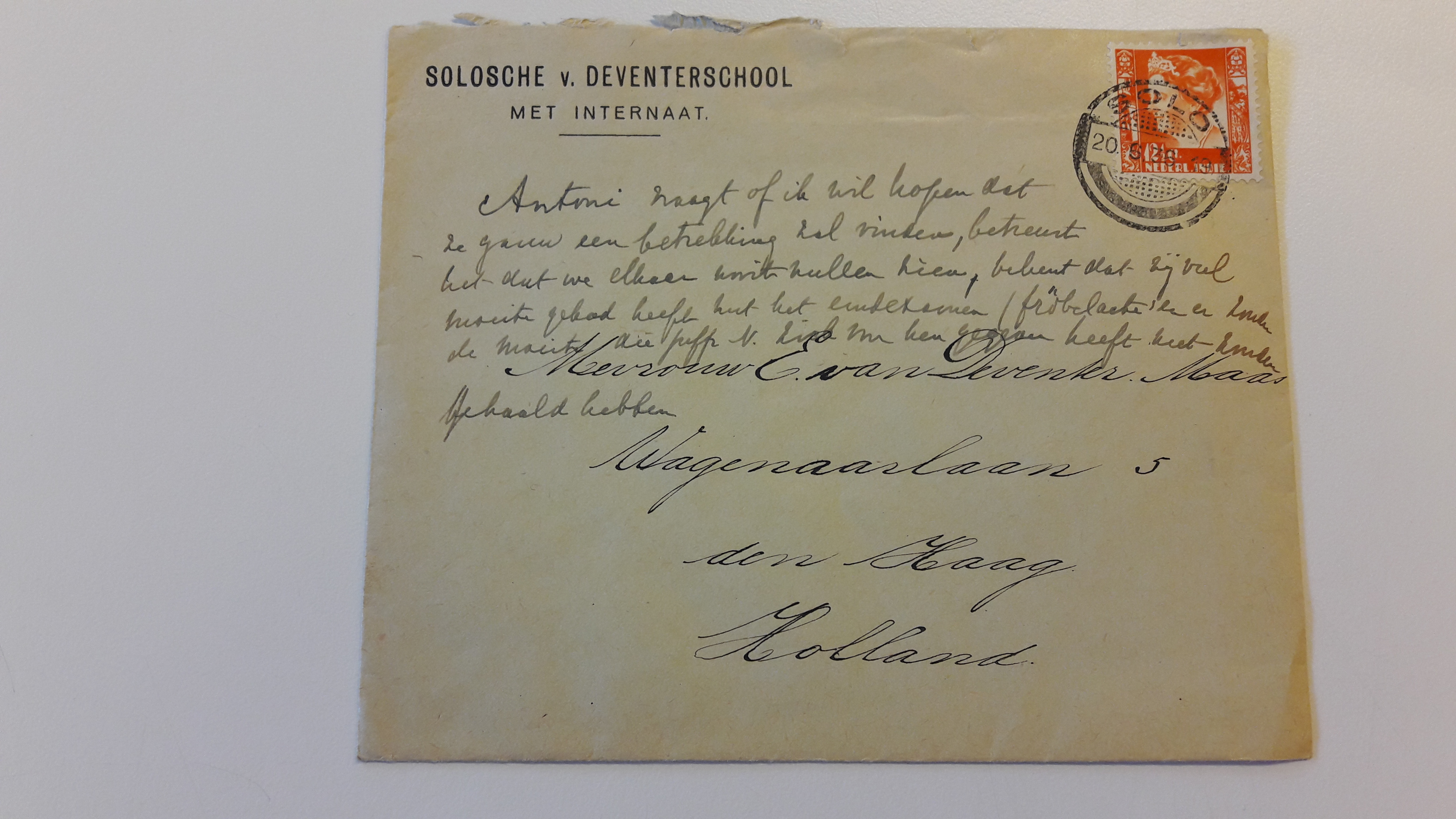

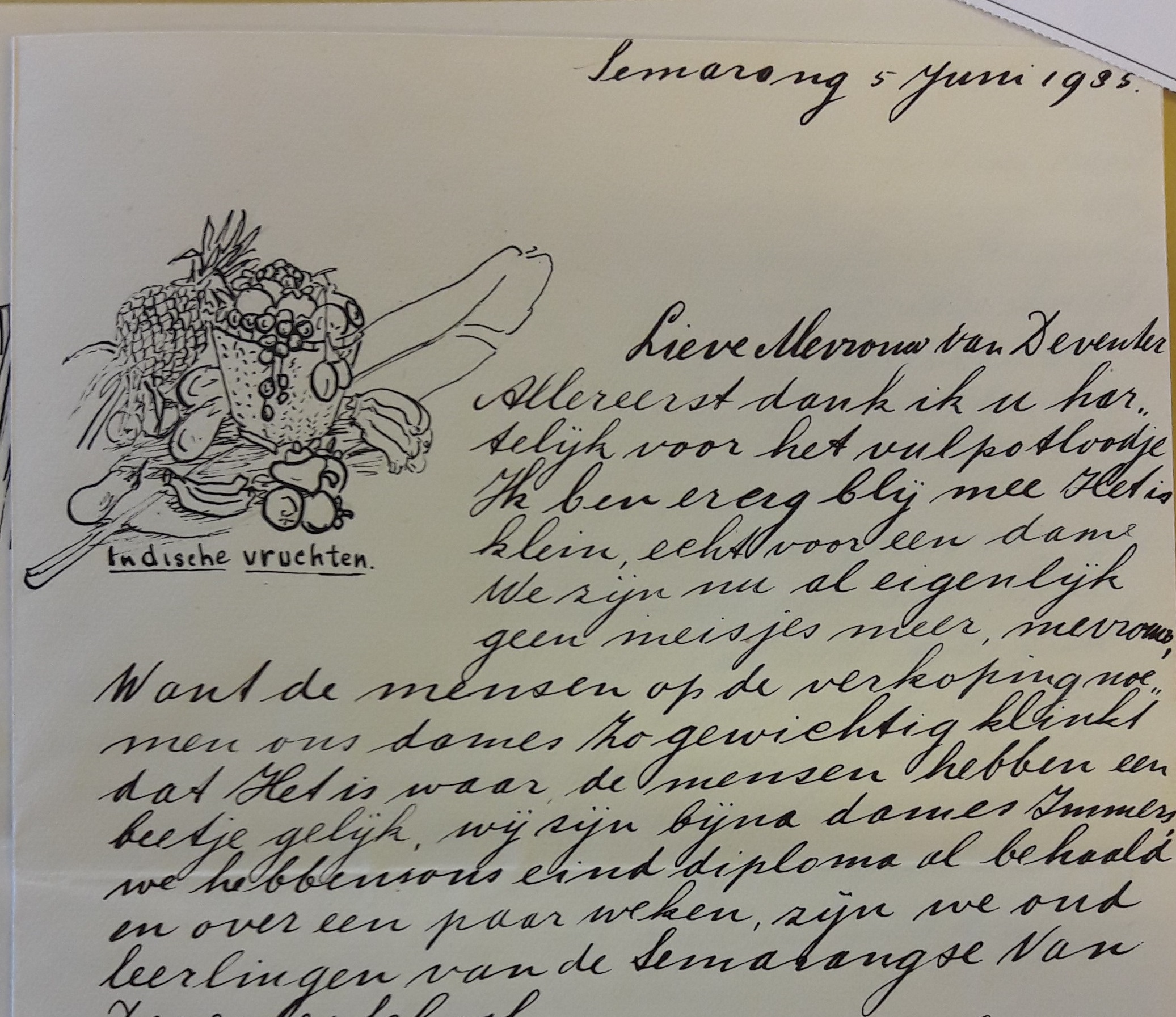

But the 1930s were also a time of deep crisis, and many of these young women were aware of the fact that obtaining a paid occupation might be difficult. Antoni, for instance, pleaded to Mrs. Van Deventer “Will you hope for us, Ma’am, that we can get employment soon, because nowadays ’tis hard to get employment.” (see picture 1: Antoni’s envelope with comments by Mrs. Van Deventer on it). “If, in the future, I stay at home, if I can’t get work, because nowadays it is hard to seek work,” commented Soemari, “then I am going to draw. I love drawing, especially children’s figures.” (see picture 2 with the drawing).

I could go on and on. I know that these are not “typical” Javanese girls, and that they must have been caught between their dreams and the realities of being colonial subjects, and women. However, I cannot help thinking that their wishes, however far-fetched or coloured by their special position in Javanese society, should be passed on to posterity. So that we will not forget those rare voices of indigenous girls and women from the past…